Aditya-L1: India 'Carefully Choosing Objectives' To Expand Footprint In Space Exploration

KEY POINTS

- Aditya-L1 will take four months to cover 1% of the Earth-Sun distance to reach the L1 point

- L1 is about 932,000 miles away from the Earth; the spacecraft will not approach the Sun any closer than this

- The spacecraft will orbit the Sun and maintain a constant, uninterrupted view of it

With its maiden solar expedition named Aditya-L1, India is cementing its position among the most advanced nations in space technology today.

Although the country is still trying to catch up with other global space powers, India's space agency is carefully choosing areas where it can make noteworthy strides to expand its footprint in space exploration.

"ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) is carefully choosing its objectives in the niche area and putting its footprints successfully. That is what's catching the world's attention," astrophysicist Sandip Chakrabarti told International Business Times.

Days after making history by being the first nation to make a soft landing on the moon's south pole, India successfully launched the Aditya-L1 mission to the Sun from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh on Saturday.

"After the success of Chandrayaan-3, India continues its space journey," Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said about the back-to-back milestones.

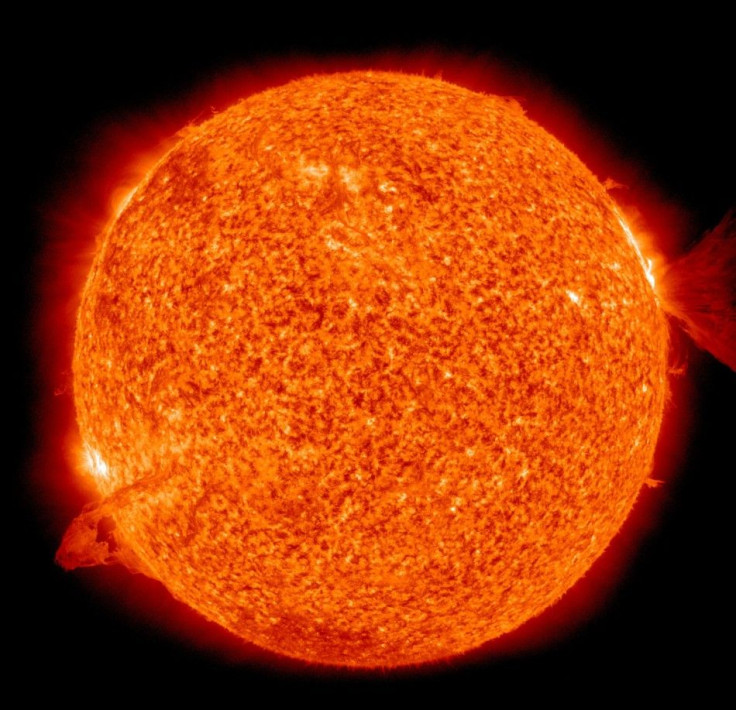

Aditya-L1 — ISRO's first space-based mission to study the star nearest to Earth — will take four months to cover 1% of the Earth-Sun distance and reach the intended Lagrange point L1, which is about 932,000 miles away from the Earth. The spacecraft will not approach the Sun any closer than this.

"L1 is a location in space where the gravitational forces of two celestial bodies, such as the Sun and Earth, are in equilibrium. This allows an object placed there to remain relatively stable with respect to both celestial bodies," ISRO said.

After reaching the L1 point, the spacecraft will orbit around the Sun in an irregularly shaped path and will be able to maintain a constant, uninterrupted view of the star.

Chakrabarti explained that the Aditya-L1 mission "cannot be termed as a discovery class mission" but rather a "monitoring class mission." He said the instruments carried in both the Aditya-L1 and Chandrayaan-3 missions are "generic."

"The instruments which Aditya L1 or Chandrayaan-3 carried are not enviable. These instruments are generic and the U.S. sent most, if not all, more than five decades ago," he said.

Chakrabarti believes India is still trying to match other space powers in some areas but is nevertheless making noteworthy accomplishments in the field.

"ISRO has been trying to catch up with the technological feats of its predecessors which were achieved several decades ago. The landing on the moon was one of them. Similarly reaching L1 point and orbiting around it is another feat," Chakrabarti said.

The astrophysicist noted that India's Aditya-L1 is unlike the lunar mission because "there is no gravitating object toward which the spaceship is orbiting."

"L1 is an 'imaginary point' out there where all the three forces operating on Adiya would cancel each other. Around such a cancellation point everything is difficult," he said. "Any little extra force in any direction would catapult the satellite to a far distance. ISRO has to maneuver in such a way that the Aditya reaches there in a coasting orbit, i.e., with almost zero velocity. After that it would orbit around the L1 point in an orbital radius of roughly the size of the lunar orbit and the orbital time would be around 6 months. So this technological demonstration would again push ISRO to an elite club where no other Asian nation is a member as of now."

As India continues to further its mission in space exploration, Chakrabarti believes "there is no scope for complacency."

"ISRO realizes that to attract attention it must first achieve what others did 30-60 years back. That is why ISRO is not giving much importance to scientific payloads or results," he said. "First, we must demonstrate our ability to achieve challenging feats; then science will follow. For instance, [India is] yet to carry out a re-entry of a space vehicle. I hope Gaganyaan would do that."

India also hasn't docked with another station yet. Chakrabarti hopes to see India attempt a docking with the International Space Station someday.

"Without a docking mechanism, sending Indians to the moon would not be possible. We have learned how to jettison, but not docking yet," he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.